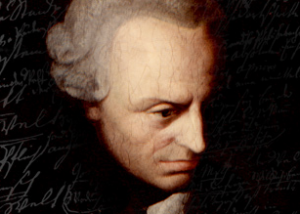

Once upon a time — say, before the 1980s or 1990s — in quite a number of countries, people led normal lives: cases were argued, judicial decisions issued, laws enacted and conflicts solved without resort to reasoning of specifically or allegedly Kantian, or indeed Enlightenment/Kantian, types. Kant’s importance was found mostly in classrooms. Over time, however — much as I regret to admit the fact — Kantian argumentation in the fields of legal and political philosophy has gone a long way towards deafening, or, to vary the metaphor, towards suffocating, most other ways of thinking. Typically Kant-fashioned concepts such as ‘dignity’ and ‘moral autonomy’ are now utterly ubiquitous — but, it is odd that while we have never had less control over our real, personal lives, we have never enjoyed so much abstract moral autonomy.

Once upon a time — say, before the 1980s or 1990s — in quite a number of countries, people led normal lives: cases were argued, judicial decisions issued, laws enacted and conflicts solved without resort to reasoning of specifically or allegedly Kantian, or indeed Enlightenment/Kantian, types. Kant’s importance was found mostly in classrooms. Over time, however — much as I regret to admit the fact — Kantian argumentation in the fields of legal and political philosophy has gone a long way towards deafening, or, to vary the metaphor, towards suffocating, most other ways of thinking. Typically Kant-fashioned concepts such as ‘dignity’ and ‘moral autonomy’ are now utterly ubiquitous — but, it is odd that while we have never had less control over our real, personal lives, we have never enjoyed so much abstract moral autonomy.

Brendan O’Neill’s recent Spiked article on abortion and free speech 1 may be taken as an example, whether the reader is pro-life (like myself) or pro-choice (like O’Neill). Moral autonomy — we are told — trumps nearly everything and justifies even the elimination of a human being (a ‘potential’ one, O’Neill would have us believe): ‘human moral autonomy’ trumps ‘human life’, which is surely odd where both are ‘human’. Besides that, O’Neill thunders against abusing the notion of ‘culture’ (‘abortion culture’, in this case), and undoubtedly he has a point, but what of ‘moral autonomy culture’? It has become a catchphrase apt to put an end to every argument, notwithstanding its want of further specification. In present-day Spain (Germany’s protectorate and poster child), as well as in other continental European, and Latin American countries, the same might be said of an omnipresent Kantian ‘human dignity’ that has all but absorbed ‘dignity’ itself to the extent of becoming one and the same thing with it (even if on hearing himself declared such a monopolist Kant would surely turn in his grave). In the wake of the German Grundgesetz quite a few constitutions have enshrined human dignity in a constitutional provision. Although I am not much in favour of enacting vague notions, good or bad, within legal texts, one must allow that the Germans had good reasons for doing so after World War II and that dignity has indeed played a role in German jurisprudence 2 , which cannot be said of Spain or other constitutional imitators of Germany.

As an academic devoted to constitutional and political theory, I have been reading English-language literature in these fields since the 1980s, and over time I think that a real change may be perceived even there along the same lines. The political authors of old wrote of liberty, politics, the rule of law, and rights and liberties, drawing mostly on English reasoning (just think of Vinogradoff, or the ‘Merry-England’ style of Jennings, or, later on, of Lord Devlin, or of Curzon 3). Now even the language and narrative have changed: if ‘an Englishman’s birthright’ has not quite yet been replaced by ‘fundamental rights’ — just you wait. My impression as a foreign reader is that when civil liberties, and the political obligation of submission to the rule of law are at stake, English writers have in fact become drier and more abstract, as well as less commonsensical and to-the-point than hitherto. Just compare any recent book on constitutional law with that of Yardley.4 Generally Kantian (or allegedly Kantian)5 ways of thinking diminish the ability to accommodate plural realities, while abusive ‘rights’ to and for everything increase social divisiveness and mistrust,6 for new horizontal fundamental rights serve in fact to protect you from your parents, teachers and doctors, rather than from a benevolent Leviathan. Flexibility and freshness of approach in facing imperfections have to make way; toleration becomes standardised if not legalised. Splitting reason in two, practical vs. pure, does violence to common sense. Overall normativism unduly ‘legalises’ politics, making it thereby more difficult to accommodate and to compromise (e.g., the case of Cataluña within Spain). Another effect is that, as in O’Neill’s reasoning, a woman’s self-contained and isolated moral autonomy acquires a right to ignore both the human life she is bearing and indeed the rest of the political community. If we insist that ‘this is entirely up to her’, it is tantamount to declaring her ‘a monad living alone’ rather than a zoon politikon. (Pope Francis has recently pointed up the ‘monadic’ nature of European fundamental rights.7)

Some months ago I enjoyed in Spiked Angus Kennedy’s brilliant ‘The Vital Importance of Being Moral’,8 yet in the end, I found myself in fact on the brink of surrendering to the vital importance of being Kantian. So surrounded are we by generally Kantian/Enlightenment narratives that sometimes it seems as if no other way of moral thinking were available to us; or as if other cultures and traditions offered no basis for dignity, conscience and ‘moral autonomy’; or as if we should be moral precisely after the Kantian fashion. Most recent liberal thinking appears generally Kantian-enlightened (Hayek, Ackermann, Dworkin, Rawls, Habermas, et al.). In a few decades, I fear that typical English ways of thinking will have become endangered species — just you wait and see.

As for Spain where I live and work, my students now take it for granted that human dignity was a Kantian creation. Thus, to be pragmatic, I advise them to expect an argument involving moral autonomy and/or human dignity the next time they happen to queue at the supermarket. Until recently, Kant used to be much studied in textbooks, but his influence on real legal or political life was negligible. Strong traditions of personal (i.e., non-political) liberty, as well as of honour, dignity, personal moral commitment and strong interpersonal relations (now vanished), were readily traceable back to centuries-old Spanish roots. Nowadays, in Spain, as indeed in many Latin American countries, any explanation of dignity, or of any sensitive question, starts with Kant in a run-of-the-mill way, utterly oblivious to the Judeo-Christian ‘imago Dei’, Catherine of Siena, Pico della Mirandola, Cervantes, Calderón de la Barca, et sic de caeteris.

I have suggested that the Kantian argument is deafening, perhaps indeed so harmful to hearing that even Spiked’s famously free thinkers seem not entirely free of its power. As for myself, upon consideration I am all but prepared to wonder if dignity and moral autonomy existed at all before Kant. The situation reminds me of Mr. Podsnap’s attribution of an alleged monopoly of every good quality to the British race in Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, which made the French visitor wonder how other countries could manage at all. ‘Human conscience’ was a discovery of Christianity. Dostoevsky does not seem to have needed Kant to proclaim dignity in his brilliant Brothers Karamazov. Melville’s robust defence of the dignity of the meanest crews of nineteenth-century whalers owed nothing to Kant. Cardinal Newman, moreover, was a staunch defender of personal conscience — and to walk along that path he does not seem to have needed Kantian crutches.

- Spiked, November 2014. ↩

- See, e.g., the LuftSiG decision of the Bundesverfassungsgericht (2006) holding that to shoot down a hijacked passenger plane, even if it might be used as a missile, is unconstitutional; or see the EUCJ ruling Brüstle v Greenpeace, C-34/10, 2011 (originated in Germany), rejecting on the basis of dignity patentability of frozen human embryos. ↩

- Sir Paul Vinogradoff, Common Sense in Law, 1914; Lord Denning, Freedom under the Law, 1949; Sir W.I. Jennings, The Queen’s Government, 1954; Lord Devlin, The Enforcement of Morals, 1965; L.B. Curzon, Jurisprudence, 1979. ↩

- David Yardley, Introduction to British Constitutional Law (1984, 6th ed.), although far less idiosyncratic and ‘Merry-England’ in approach than Jennings. ↩

- We cannot now further explore that path. As Prof. Richard Stith wrote in a letter to this author, “I continue to be puzzled at the contemporary use of Kant to defend amorality. … Kant would provide a pro-abortion argument, at most, only in support of the rare aborting woman who could say honestly ‘I myself should have been aborted in the circumstances in which I am now aborting my child.’ … He says a small child is ‘a being endowed with freedom’ long before it can act freely” (see Metaphysics of Morals, Cambridge, 1966 p. 64). ↩

- Brendan O’Neill, ‘Welcome to the trust no one society’, Spiked, 2013. ↩

- Pope Francis, speech to the European Parliament, 25 November 2014. ↩

- Spiked, 25 April 2014. ↩

I rgret to say that I know very little about philosophy or theology. I certainly don’t know anything about Brendan o’neill or Immanuel Kant. I do see the argument that Christianity in Europe is apparently dying, but it is not dead. There have been many Christian Saints and martyrs have lived and died in the diverse troubled times of the last 4 centuries. The court of human rights says that workers good and bad have rights so they cannot be sacked. the court also says that criminals have rights so they are free to prey upon the vulnerable. Yet the unborn can be aborted, the elderly or disabled or in other ways vulnerable can be put down. As for conscientious objectors, they now have to obey the law. Yes it does seem like the pursuit of0 bananas. We must pray harder for Christ’s Justice.